At Longwood, our commitment to environmental stewardship goes beyond our vibrant blooms and flourishing landscapes. It extends deep into the heart of nature itself, where the seeds of countless plant species hold the key to preserving biodiversity for generations to come—and in such physical places as our own seed bank, a key component of our conservation work. With our recent award of a competitive grant from the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources as part of the Wild Resource Conservation Program, we are thrilled to be able to grow our efforts in preserving more species of conservation concern through the expansion of our seed bank. This grant will help us expand from a daily use seed bank that supports a variety of horticultural purposes at the Gardens, and to focus dedicated space to a conservation seed bank with long-term storage of regionally and globally rare native plants from Pennsylvania. Our to-come conservation seed bank space—which will be the first of its kind in Pennsylvania to support the long-term storage of seeds—will act as a time capsule for storing rare species and their genetic diversity, opened only when absolutely necessary to help prevent extinction or in case of a disaster.

If humans want to make sure plants—and ultimately our own species—are around in perpetuity, we need to understand how to grow plants, both now and in the future—and our work, taking place in our growing seed bank and beyond, is dedicated to such extraordinary efforts. Preserving and growing species of conservation concern encompasses both the need to prevent the extinction of species and to make sure that there is enough genetic diversity within a species. While this can be done in a plant’s native range, such as work focused on conserving the pink lady’s slipper orchid in the Wissahickon Valley—experts also do this in a controlled setting outside of the plant’s natural habitat—what is referred to as “ex situ” conservation, and includes the use of seed banks.

For a seed bank to be useful, it needs to be maintained to extremely high standards to ensure the preservation of plant genetic diversity. This requires meticulous records, collection policies, and constant conditions. For these seeds that were collected on a trip to China, the label includes a serial number, the people that collected the seed, the scientific name of the plant, and where the seed originated. Photo by Peter Zale.

Typically, ex situ conservation is done through two methods: Growing plants in gardens as a living collection or storing seeds in a seed bank to be planted later. While both have their own advantages, and are often best used in combination, seed banks have far less visibility to the public than the plants of conservation value being grown in a conservatory or garden. Storing and preserving seeds is a crucial tool for conservationists, as it offers the most controlled and secure way to actively contribute to the preservation of plant species. In a worst-case scenario, if the last known population of a species is lost in the wild, due to a natural disaster (or human mediated one), having seeds of that species in a seed bank enables us to restore the plants to the environment and prevent extinction. With the realization of this grant, we will expand our seed bank footprint by nearly 80 percent, thereby adding enough space to store thousands of additional packets of seeds for long-term conservation.

Galearis spectabilis (showy orchis) is among the five native orchids we will be including in our initial conservation seed bank collections. Although this species is among the most common native orchids in our area, it rarely sets seeds and is nearly impossible to grow from seed. We hope our initial efforts to collect seeds will help us understand the ecological idiosyncrasies of this species. Photo by Duane Erdmann.

A seed bank is a place with specific conditions (low temperatures, low moisture, etc.) where experts store seeds or cuttings (through cryopreservation) to preserve genetic diversity. Although they are dormant, seeds are living things. Understanding how to keep seeds alive, and understanding what it takes to get them to germinate, can be extremely challenging and complex. While some seeds can be seed-banked, other types of seeds—typically those from the tropics — cannot. This complication stresses the importance of gardens using both living collections and seed banks together in conservation-related efforts. Researching the storage and germination requirements of seeds of different species can be a Herculean effort.

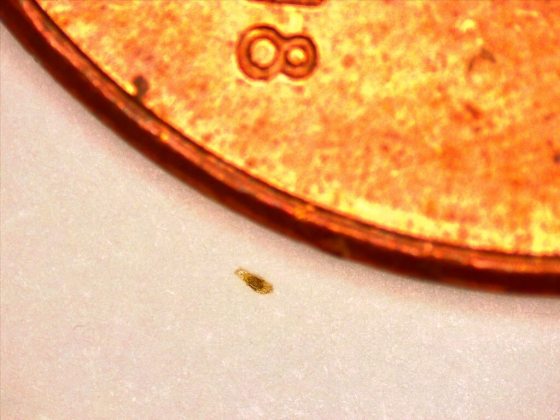

The dust-like seeds of orchids are notoriously small. This botanical family has the smallest seeds of any other plant family—and often each flower can produce millions of them. Here is an orchid seed next to a penny. Photo by Ashley Clayton.

This tiny vial (1.5 mL or less than 1/3 a teaspoon) contains thousands and thousands of orchid seeds. Our expanded conservation-focused seed bank will be able to support rare Pennsylvania species and native orchids. Photo by Peter Zale.

There is hope, however, as there are experts dedicated to studying and conserving seeds, along with many seed banks around the world, from the Millennium Seed Bank in the UK, to the Parque de la Papa in Peru, to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, to the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Colorado, to our own here at Longwood.

Conserving genetic diversity within a species is important. In fact, this is the reason the first seedbank was started. Nikolai Vavilov started the first recorded seed bank to protect genetic diversity of agricultural crops, with the goal of preventing future famines. He accurately reasoned that the secrets within genes could protect agricultural plants from potential diseases or pests. Ensuring genetic diversity in these plants was an investment in the future, as those genes might improve yield or flavor, or even support drought tolerance. This concept set in motion a whole new field of study and effort—collecting and preserving seeds to protect diversity for the future.

Platanthera peramoena (purple fringeless orchid) is among the native plants we will be working with the preserve in ex situ conservation. We chose this species because it is known to enter “prolonged dormancy,” a condition well-documented in orchids. This means it doesn’t appear or flower every year. We hope that our efforts to collect seeds of this species will provide an additional means of conserving this species and provide more information about its behavior. Photo by Peter Zale.

Our conservation horticulture team studies and teaches others how to conserve and grow plants that are integral to the planet—from around the world to our own backyard. The recently received grant will help fund our important conservation work and help support and grow our seed banking facilities and efforts. Building off an eight-year study to conserve native species, led by Longwood’s Associate Director, Conservation Horticulture and Plant Breeding Peter Zale, Ph.D., we will be working with collaborators from the Pennsylvania Conservation Alliance, Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program, and Pennsylvania Department of Conservation & Natural Resources’ Bureau of Forestry to wild-collect seeds from rare Pennsylvanian species and several native orchid species.

Orchids are one of Longwood’s most important collections, and a foundational group of our conservation horticulture efforts. The plants we will be researching include: Polemonium vanbruntiae (Appalachian Jacob’s ladder), Taenidia montana (mountain parsley), Trifolium virginicum (Kate’s mountain clover), Calopogon tuberosus (tuberous grasspink), Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens (greater yellow lady’s slipper), Galearis spectabilis (showy orchis), Platanthera ciliaris (yellow fringed orchid), and Platanthera peramoena (purple fringeless orchid).

Calopogon tuberosus (tuberous grasspink) is a native orchid species found throughout Pennsylvania. We chose five different native orchids from diverse ecosystems to seed bank. Through seed bank-associated research, we will test the hypothesis orchids from different habitats have seeds that respond differently to seed bank conditions. Photo by Matthew Ross.

These interesting and beautiful plants are incredibly valuable to our native landscapes, often important flowers for pollinators, and they are of conservation concern. The first three species listed are among the rarest and most vulnerable species native to Pennsylvania and need all the help they can get both within and beyond their native habitats. The last five species are all native orchids found in diverse habitats throughout Pennsylvania. Information about seed banking tolerance is unknown for many orchids, so we chose species from widely varying habitats to test the hypothesis that habitat preference will influence seed tolerance to seed bank conditions. This means they need help to ensure they are around in the future.

We have been researching native orchid propagation for years. These images represent the general steps in propagating a Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens (greater yellow lady’s slipper). Flowers are hand-pollinated in the wild. After the seeds are produced, they are collected and put into a growth medium in sterile laboratory conditions. The far right image shows what the initial seedlings look like after the seeds germinate. Our seed bank efforts will also help support our native orchid propagation research. Photos by Peter Zale.

After the seeds are collected from these diverse native species, our experts will then test the seeds to understand how viable they are (how many of them are able to germinate), evaluate different methods to learn what it might take to get the seeds to germinate successfully, and determine if the seeds are able to be seed banked. Over the next few years, we will find out the answers to these questions, and we will share the results with practitioners, science professionals, and our guests. In time, through these collaborative efforts and research, our goal is to securely bank the seeds for all the rare and endangered species in the state of Pennsylvania, in addition to banking seeds for the region and other parts of the world in need of this resource and reserve.

As we peer into the future, we stay steadfast in our commitment to seed banking and broader conservation efforts. We envision a world where the seeds we collect today blossom, and are planted back into thriving ecosystems, enriching the planet with the beauty and diversity of plant life. By nurturing these seeds of conservation, we sow the promise of a more resilient, inspiring, and harmonious coexistence with nature.

Editor’s note: Learn more about Longwood’s work in seed science—and its far-reaching effects from Associate Director of Conservation Horticulture and Plant Breeding Peter Zale, Ph.D.—during our Science Series: Seed Science talk on April 20 in the Ballroom (free with Gardens Admission).